Google Cloud's outage should not have happened, and they seem to be missing the point on how to avoid it in the future by Eduardo Bellani

Another global IT outage happened, this time at Google Cloud Platform (team 2025), taking down with it large swaths of the internet (Zeff 2025). Like my previous analysis of the CrowdStrike outage, this post critiques GCP’s root cause analysis (RCA), which—despite detailed engineering steps—misses the real lesson.

Here’s the key section of their RCA:

Google and Google Cloud APIs are served through our Google API management and control planes. Distributed regionally, these management and control planes are responsible for ensuring each API request that comes in is authorized, has the policy and appropriate checks (like quota) to meet their endpoints. The core binary that is part of this policy check system is known as Service Control. Service Control is a regional service that has a regional datastore that it reads quota and policy information from. This datastore metadata gets replicated almost instantly globally to manage quota policies for Google Cloud and our customers.

On May 29, 2025, a new feature was added to Service Control for additional quota policy checks. This code change and binary release went through our region by region rollout, but the code path that failed was never exercised during this rollout due to needing a policy change that would trigger the code. As a safety precaution, this code change came with a red-button to turn off that particular policy serving path. The issue with this change was that it did not have appropriate error handling nor was it feature flag protected. Without the appropriate error handling, the null pointer caused the binary to crash. Feature flags are used to gradually enable the feature region by region per project, starting with internal projects, to enable us to catch issues. If this had been flag protected, the issue would have been caught in staging.

On June 12, 2025 at ~10:45am PDT, a policy change was inserted into the regional Spanner tables that Service Control uses for policies. Given the global nature of quota management, this metadata was replicated globally within seconds. This policy data contained unintended blank fields. Service Control, then regionally exercised quota checks on policies in each regional datastore. This pulled in blank fields for this respective policy change and exercised the code path that hit the null pointer causing the binaries to go into a crash loop. This occurred globally given each regional deployment. (team 2025)

A central database had a nullable field. A new policy change injected a blank value into this field. The application code didn’t expect that value to be null, which caused a crash loop across all regions. The bug wasn’t caught during rollout because the faulty code path required a policy trigger that never occurred in staging

Sound familiar? It should. Any senior engineer has seen this pattern

before. This is classic database/application mismatch and the age-old

curse of NULL(McGoveran 1993). With this in mind,

let’s review how GCP is planning to prevent this from happening again:

1. We will modularize Service Control’s architecture, so the

functionality is isolated and fails open. Thus, if a corresponding

check fails, Service Control can still serve API requests.

2. We will audit all systems that consume globally replicated

data. Regardless of the business need for near instantaneous

consistency of the data globally (i.e. quota management settings are

global), data replication needs to be propagated incrementally with

sufficient time to validate and detect issues.

3. We will enforce all changes to critical binaries to be feature flag

protected and disabled by default.

4. We will improve our static analysis and testing practices to

correctly handle errors and if need be fail open.

5. We will audit and ensure our systems employ randomized exponential

backoff.

6. We will improve our external communications, both automated and

human, so our customers get the information they need asap to react

to issues, manage their systems and help their customers.

7. We'll ensure our monitoring and communication infrastructure remains

operational to serve customers even when Google Cloud and our primary

monitoring products are down, ensuring business continuity.

These are all solid, reasonable steps. But here’s the problem: they already do most of this—and the outage happened anyway.

Why? Because of this admission, buried in their own RCA:

…this policy data contained unintended blank fields…

They are treating a design flaw as if it were a testing failure.

The real cause

These kinds of outages stem from the uncontrolled interaction between application logic and database schema. You can’t reliably catch that with more tests or rollouts or flags. You prevent it by construction—through analytical design.

- No nullable fiels.

- (as a cororally of 1) full normalization of the database (The principles of database design, or, the Truth is out there)

- formally verified application code(Chapman et al. 2024)

Conclusion

FAANG-style companies are unlikely to adopt formal methods or relational rigor wholesale. But for their most critical systems, they should. It’s the only way to make failures like this impossible by design, rather than just less likely.

The internet would thank them. (Cloud users too—caveat emptor.)

References

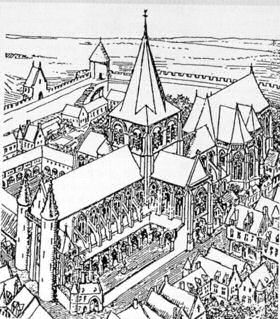

Figure 1: Boulogne-sur-Mer cathedral: destroyed by the Revolution. The cathedral in 1570, drawn by Camille Enlart (1862-1927)